Harry Borden

Harry Borden is one of the UK’s finest portrait photographers and his work has appeared in many of the world’s foremost publications including The New Yorker, Vogue and Time.

Harry won prizes at the World Press Photo awards (1997 and 1999) and was a judge in the contest in 2010 and 2011.

In 2005 he had his first solo show at the National Portrait Gallery in London and the organisation currently have 117 of his prints in their archive. In 2014 he was awarded an Honorary Fellowship by the Royal Photographic Society.

In January 2017, his book “Survivor: A portrait of the survivors of the Holocaust, was published by Octopus. Alain de Botton declared it, “A masterpiece and deeply moving” and Martin Parr said “something really to behold, a substantial project of some real depth and authority. By flicking through the pages you can sense the amount of research, patience and hard work that has been invested. The portraits, as always with Borden are simple, effective and very telling.” In May 2018 it was judged one of the year’s 10 best photography books by the Kraszna-Krausz Foundation Book Awards.

Harry Borden’s signed limited editions are available to purchase in a choice of physical size options. As you scroll down this page you will be able to view the photographs and the stories behind them—which are fascinating. Editions are offered in number order, so early-bird purchasers have the opportunity to secure the coveted number 1 print in an edition.

Harry is active on social media and I would encourage you to follow him on Instagram. You will find him at @harryborden. If you see a photograph of Harry’s that we aren’t showing on the website and would like to own it, just get in touch with us at the gallery and we can arrange a print for you.

Visit the virtual gallery

Click on the green button below to view our beautiful virtual reality gallery featuring a selection of Harry’s images framed and on display.

This isn’t a replica of our physical gallery space—far from it. It is a gallery that we have designed from scratch and that only exists in the virtual world. The space consists of three elements: a large central room with high ceilings and white walls, a mezzanine floor accessed by a spiral staircase, and a smaller, more personal viewing room with a feature brick wall. You can navigate around the space simply, and click on individual artworks to view price and size information.I hope you enjoy experiencing the virtual collection.

The limited editions

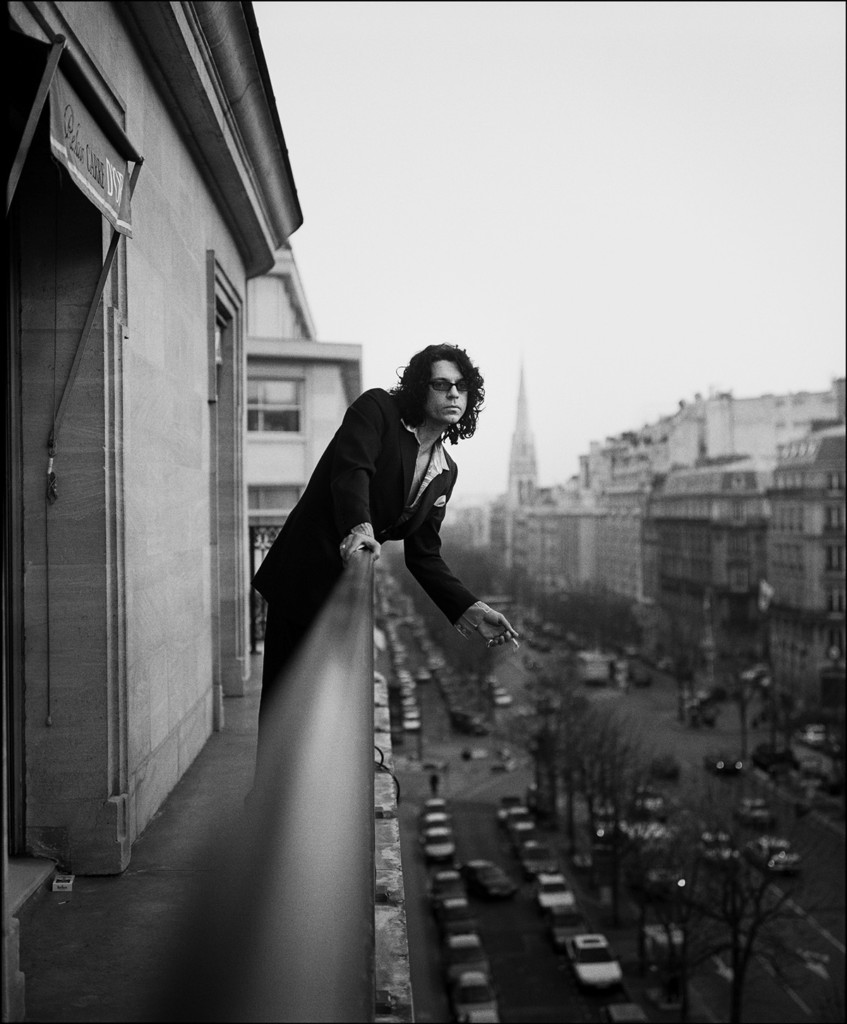

Michael Hutchence

Paris, March 1997.

Michael Hutchence pauses for a cigarette on the balcony of his hotel on the Champs Élysées, Paris, March 1997

This portrait of Michael Hutchence has become one of Harry Borden’s best known images. Harry recalls a memorable week spent with the tragically short-lived INXS singer: “In March 1997, I was asked by The Observer to photograph him in Paris, where he was promoting INXS’s latest single, “Elegantly Wasted”. It was a great commission and involved me staying at a really nice hotel on the Champs-Élysées for a week – where Hutchence was also staying. However, as we had to fit the shoots around him doing interviews and performing on pop shows, there was a lot of waiting around. I saw him perform the new single over and over again. He was, at that time, 37 years old and had been in the business for more than 20 years, but was still a mesmerising performer and had a lithe, panther-like quality. He had a great voice and his on-stage presence helped make the band really successful.

One day I was out on the hotel balcony, trying to keep out of the way while he was doing a television interview in his room. At one point, he came out to have a cigarette. I had my camera with me and he just posed for me briefly, without either of us actually acknowledging that he was posing. As he looked past me, into the distance, his mind seemed to be somewhere else. It was a genuine moment. Having got to know Hutchence quite well during my week in Paris, it was a shock when, just nine months later, he was tragically found dead in a Sydney hotel room. The official verdict was suicide.

The following year, the balcony shot was shortlisted for the John Kobal Portrait Award, and the Australian National Portrait Gallery contacted me to say they wanted it in their collection. Later, some of my other Michael Hutchence images featured on the sleeve of his posthumously released solo album. Since then, the balcony portrait has taken on a life of its own and has become one of my best-known photographs. The fact that Hutchence had died in a hotel room has undoubtedly given the portrait added poignancy. “

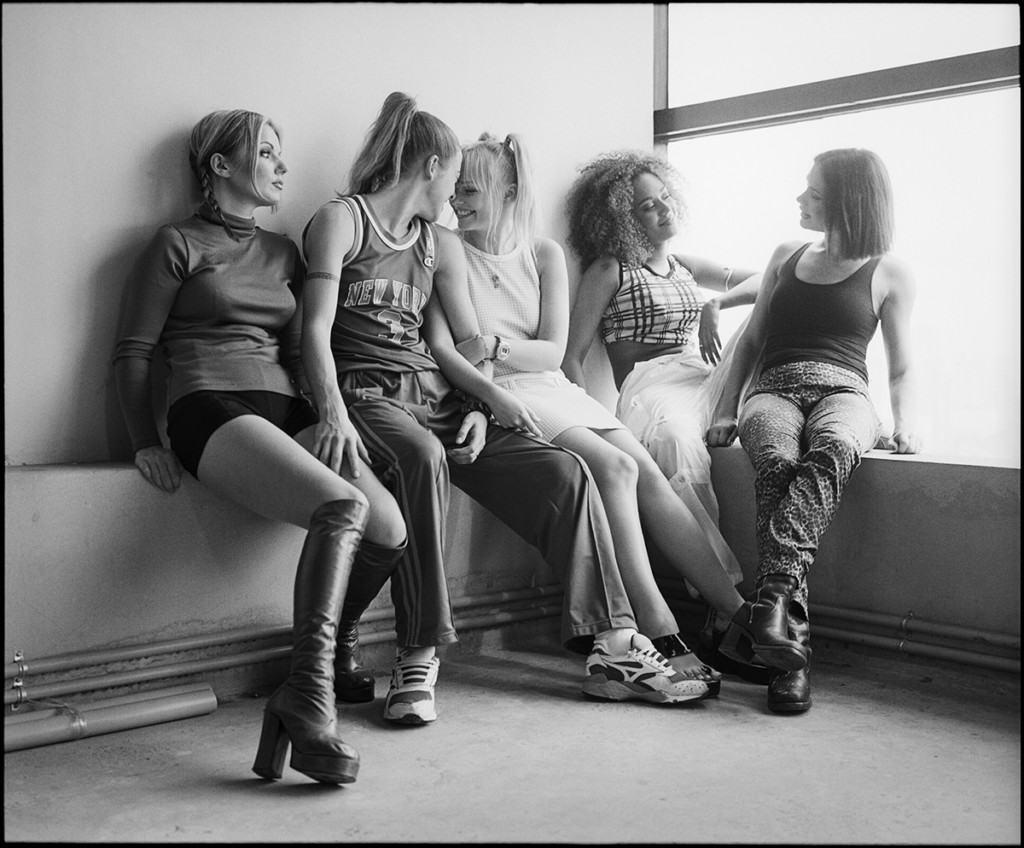

The Spice Girls

Bangkok, 1996.

The Spice Girls, Bangkok 1996. L to R: Geri Halliwell, Melanie Chisholm, Emma Bunton, Melanie Brown, and Victoria Adams (later Victoria Beckham)

Harry Borden photographed the Spice girls on four occasions and this is his favourite Spice Girls image. He explains: “The location for the shoot was a half-built tower block in the centre of Bangkok, chosen because their record company’s offices were on a lower floor of the building. After shooting a number of pictures on the roof, we came down to the office and they sat down, exhausted by the heat. I immediately saw that this scene would make a much better picture than the others I’d taken. So I quickly asked them to hold their positions and shot a few frames, using my Fujifilm 6×7 rangefinder, with Kodak Tri-X film.

There’s a wonderful line going through it, partly because of the way they are touching or linking arms, and the interplay between the two pairs of girls looks very natural. I also like the variation in light; Geri, on the left, is lit like a figure from a Renaissance painting, while Victoria on the other side of the frame is backlit. The fact that Geri is looking slightly distant is also appropriate; she was older and more worldly than the others and went on to leave the group in 1998. The picture only came about because I was alive to the situation and didn’t switch off – and shows that sometimes magic happens when you’re not trying too hard. “

A print is now in the permanent collection of The National Portrait Gallery.

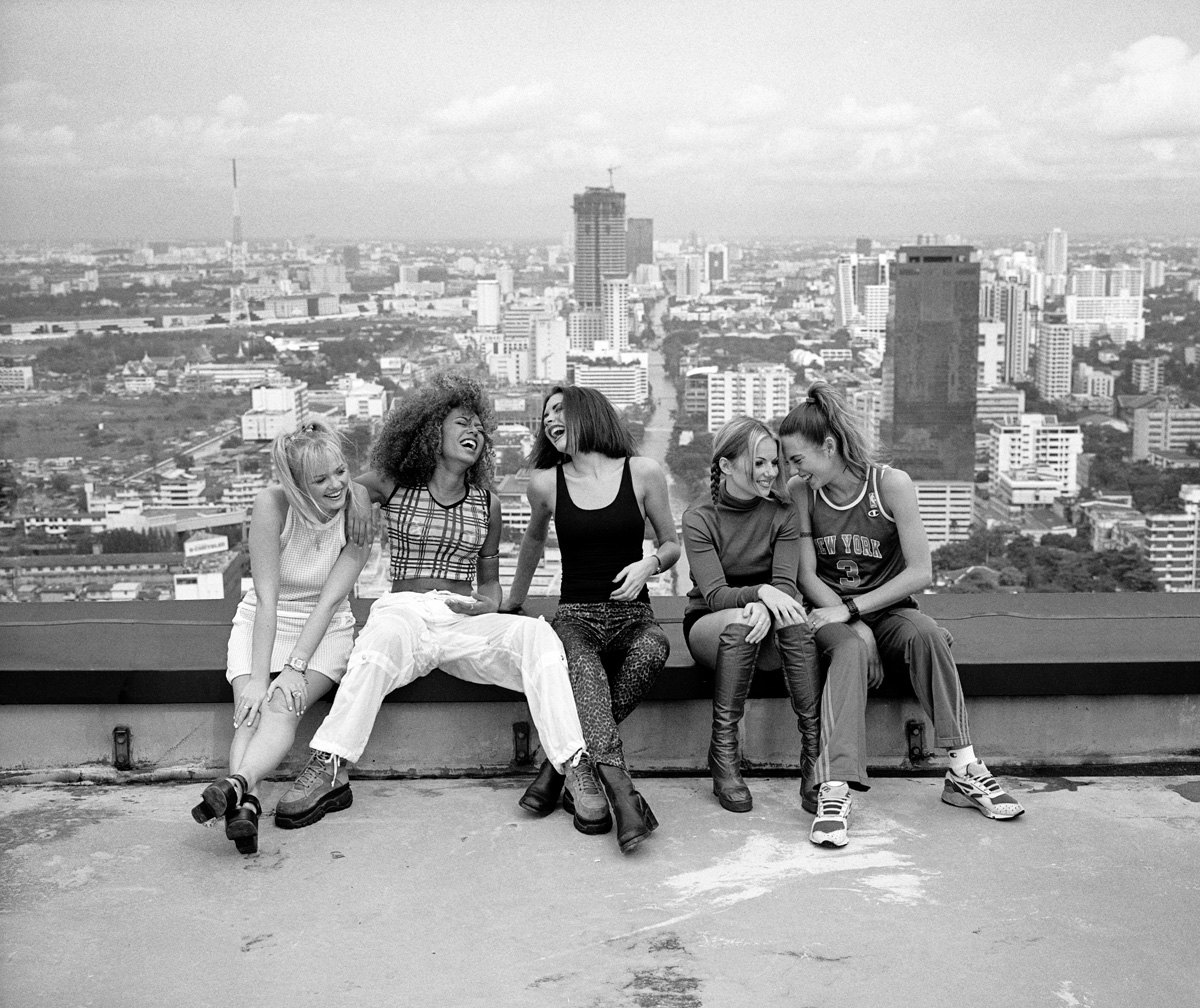

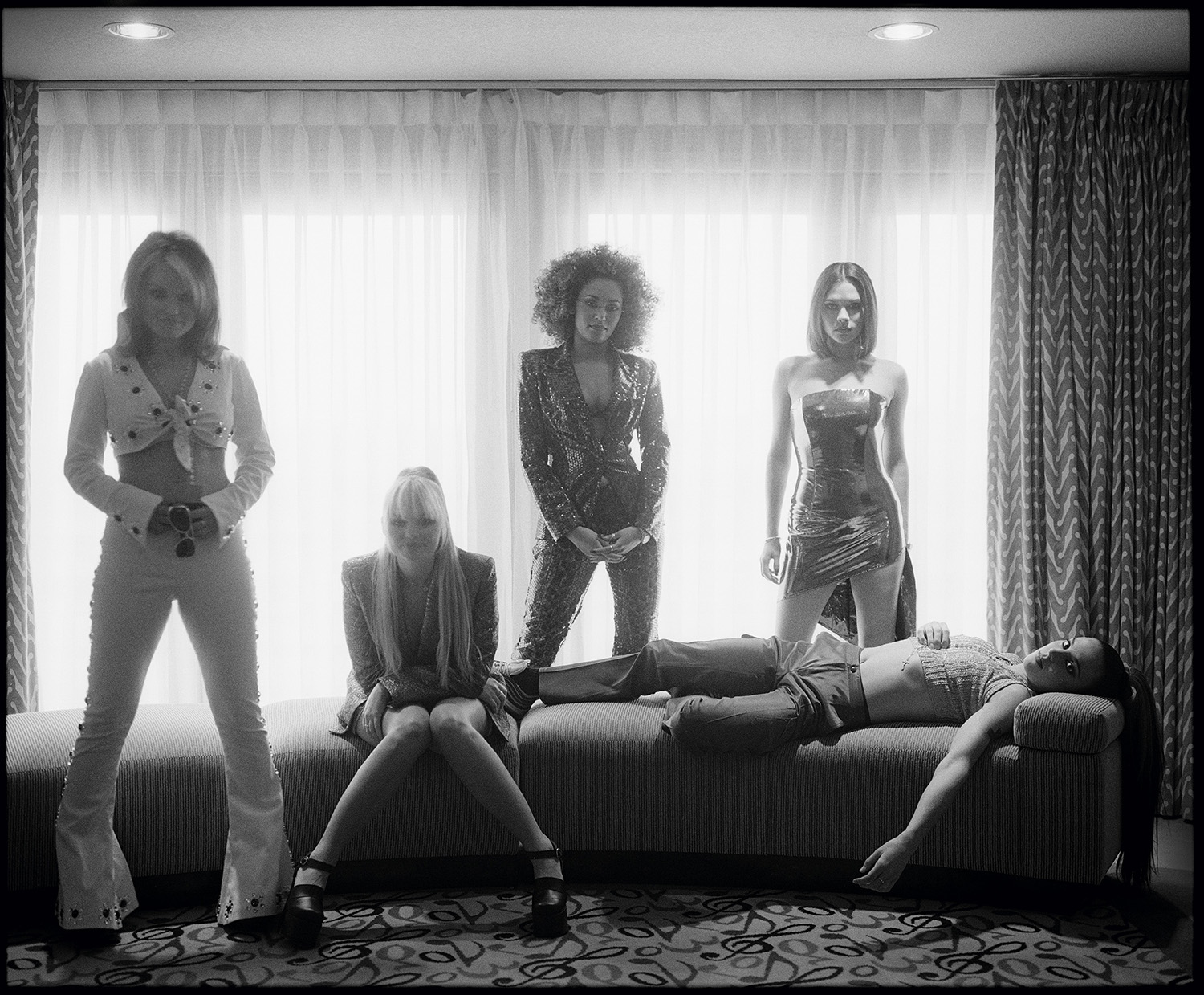

The Spice Girls

Las Vegas, 8 December 1997. A set of five individual portraits

Harry recalls the shoot: “The ageing diary pages from my Filofax confirm it was my craziest week ever. Monday, I shot the Girls in Las Vegas. Tuesday, I flew to Los Angeles for artist Frank Stella. On Wednesday, I travelled to the East coast to shoot Joseph Heller in New York and finally a jaunt to Chicago for Barry Manilow. All without an assistant.

These portraits were taken in my hotel room, lit with a single tungsten ‘redhead’. I realise now I was influenced by Corinne Day’s grungy portrait of Kate Moss for Vogue June 1993.

By this stage the Girl Power Juggernaut was unstoppable, the previous evening I’d watched them win a Billboard Award for best album at the Hard Rock Hotel and Casino. As usual, I didn’t get long but they were fun and very professional.”

Lenny Kravitz

Bahamas, 1998.

Lenny Kravitz, The Bahamas, 1 July 1998.

Harry explains: “This was taken in the Bahamas. I had first photographed Lenny seven years before for the NME. That occasion was his first UK interview and he and his manager came to my flat in Bethnal Green. We remembered the shoot and it was good to reconvene in such an exotic location.

He was making a video so there was a lot of hanging around. We stayed at the Compass Point Beach resort, and our bedrooms were on stilts next to the beach. It was basically a holiday punctuated by the shoot.

Although reluctant to be shot without his sunglasses, he was beautiful, cool and very easy to photograph. Eventually I got him in the sea and after taking the obligatory statuesque images of his perfectly proportioned body, I shot this picture. The boat on the horizon and him lower in the water, the image had narrative and a sense of mystery.

I shot this on a Fuji 6×7 Rangefinder on Tri-X Film. Sometimes less is more.”

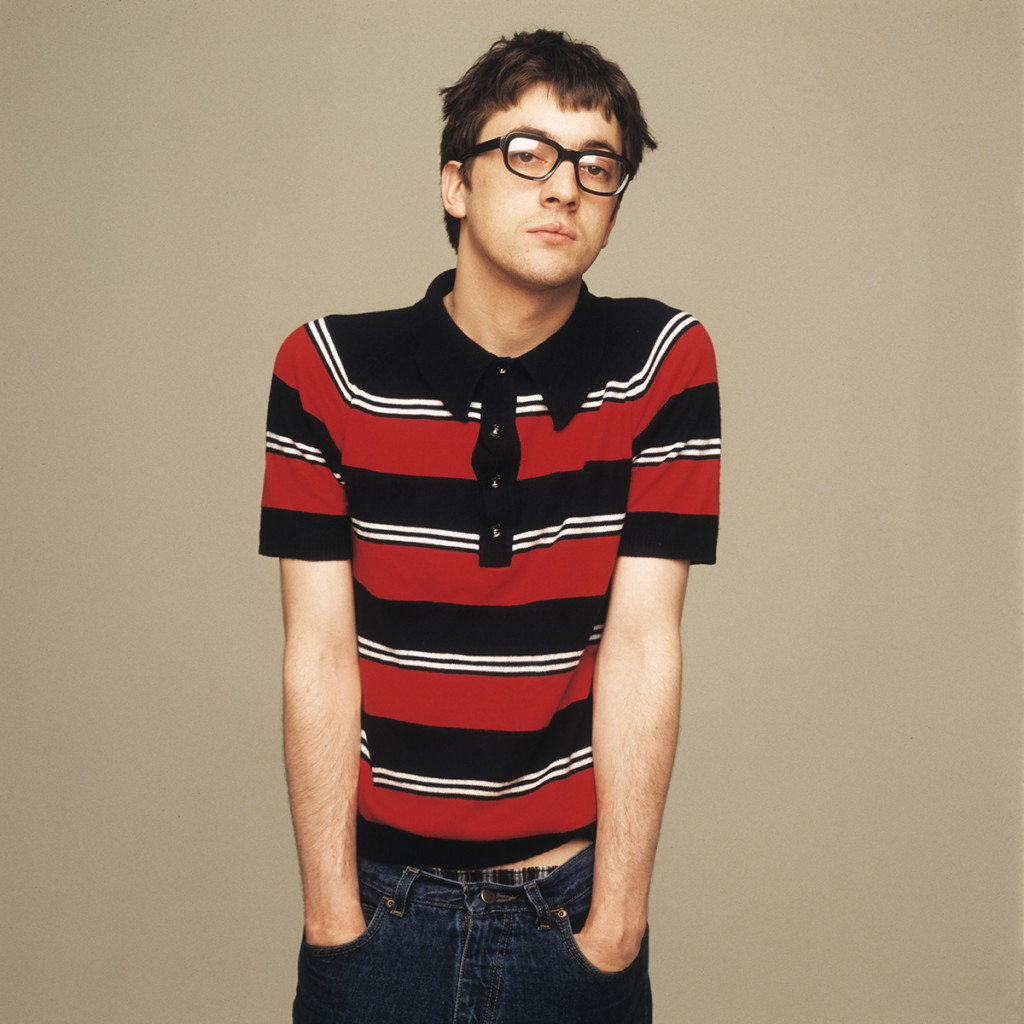

Jarvis Cocker

London, 1998.

Jarvis Cocker, Waterlow Park, London, March 1998

Harry Borden recalls the session with the Pulp frontman: “I took this photograph in March 1998. By that time Pulp had recorded two major hit albums: His ‘n’ Hers (1994) and Different Class (1995), which featured several iconic singles including ‘Common People’.

By this stage Jarvis was a superstar, established as part of the cultural landscape and featured frequently in the newspapers. I was doing the shoot for the Observer and he was being interviewed by journalist Lynn Barber at her house in Highgate, London. Using my Hasselblad, I took some pictures around the house, including in her daughter’s bedroom. The original idea was to move on and shoot some pictures in Highgate Cemetery, but I felt it wasn’t really appropriate for him as he wouldn’t have fitted into that Gothic environment.

Instead we went to nearby Waterlow Park and shot more images there. Towards the end of the shoot I asked him to zip up the hood of his snorkel parka coat, so only his big, reflective glasses were visible. I liked the idea of being confronted with someone famous and playing with the fact that it’s really them. I was concerned his face would be too dark, so I used a handheld exposure meter to take a reading of the light going into the hood. By exposing only for his face, the line of trees in the background was blown out because it was overexposed. The result was a graphic and intriguing picture.

It is possible that I had David Bailey’s portrait of Mick Jagger in a fur hood in mind when taking this picture. Rather than just copy a famous image, I try to take an idea and use it as a basis to create something that is different and original. This way, rather than getting a pastiche, you get a genuine moment. The line of trees in my picture gives it a kind of municipal ordinariness that suits Jarvis’s style and takes it on to another level.”

Radiohead

London, 2007.

Radiohead, Holborn Studios, London, 2007

Harry Borden recalls the session: “In 2007 I photographed Radiohead for the Observer Music Monthly. They were about to release their seventh album, In Rainbows. They were also a more cerebral outfit than most other bands, so I thought carefully about how I would photograph them. I definitely didn’t want to turn up completely unarmed to photograph a band of hip and savvy people. The Observer had hired a room at Holborn Studios in north London, but I aimed to do something different from the average studio shoot. I wanted to approach it from an alternative angle, to include some element of performance and encourage the band members to be fully engaged and collaborative. With all that in mind, I came up with the concept of allowing the band to photograph themselves. I liked the idea because they seemed empowered and in control of their destiny, so it seemed an appropriate approach, as well as being quite funny. I talked it through with the magazine’s editor, who agreed, then bought an infrared cable release so the band could fire the camera’s shutter.

When they arrived for the shoot, I explained the idea to them and they were really up for it, so I went ahead with setting it up. We had the biggest studio at Holborn. The equipment included a splendid block and tackle arrangement that I’d often admired, so I decided to incorporate it in the shoot. I attached one light to it with an Octa softbox, which I love using. I only used one light because when it comes to lighting I always believe that less is more. My Canon EOS 1Ds Mark II was set up on a tripod with a 50mm lens attached. I asked the band to stand under the Octa and arranged the band members with lead singer Thom Yorke at the front. Then I gave him the infrared cable release asked him to point it at the camera. I let him take the pictures until the memory card was full. One of those images was used on the cover of Observer Music Monthly. After we had done that scenario, I borrowed my assistant’s 1DS Mark II and asked the band to stand in the same places as they were when taking their own picture. Then I switched the radio sync to my assistant’s camera and shot the whole set-up from a different angle. I got some frames of my assistant standing by the camera, but ultimately the set-up worked best when it was just the band taking pictures. My favourite shot, shown here, has Thom Yorke giving a knowing look to my camera.

This picture was used inside the magazine. As well as being something different and eye-catching, it works well because I think the picture references the kind of band Radiohead is.

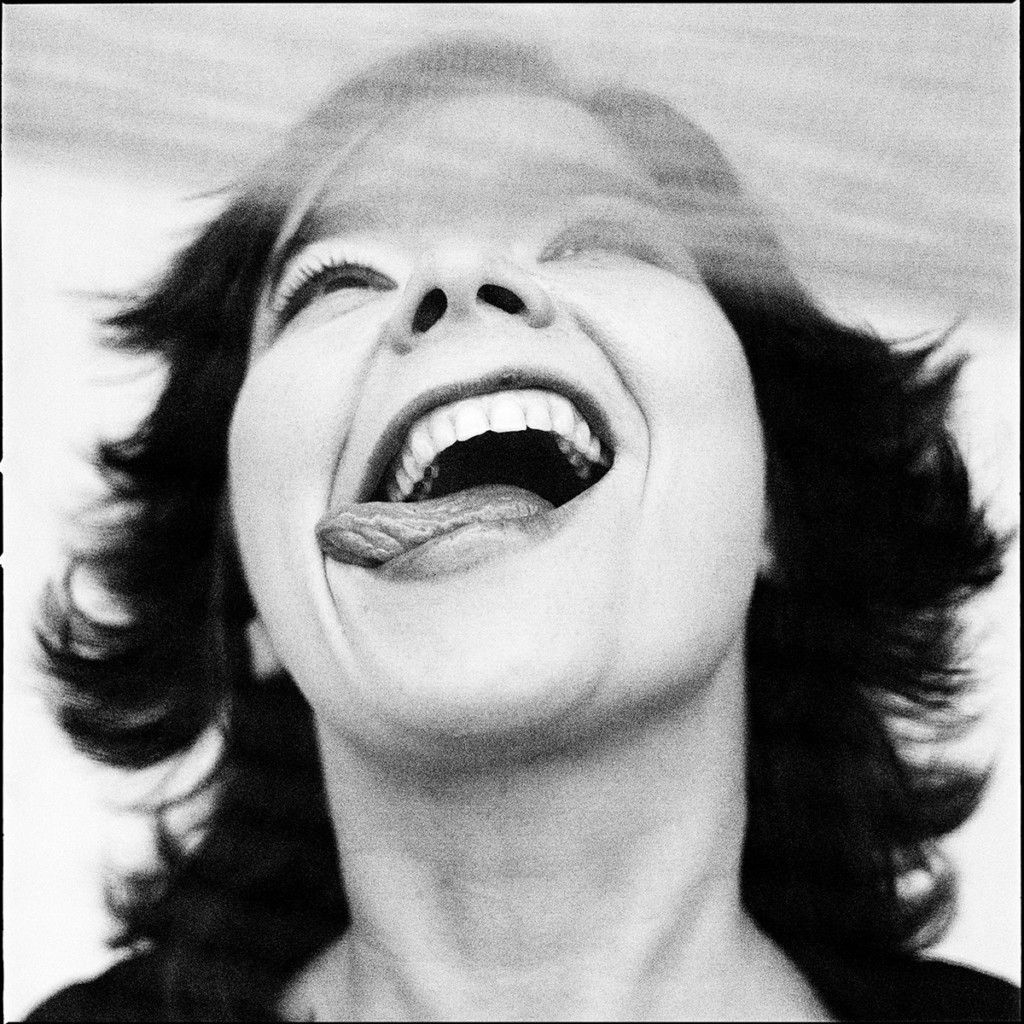

Bjork

Reykjavik, Iceland, 1998.

Bjork, Reykjavic, Iceland, 24 September 1998

Harry recalls the shoot with Björk: “Visually sophisticated and engaged in the process, it’s not enough to get just a ‘good’ portrait of Björk. I’m sure every photographer who takes her picture has the image in their portfolio.

This was from a memorable trip to Iceland with Lynn Barber for the Observer. Although I was only allocated 20 minutes, this photograph was lucky enough to win a World Press award in 1999. It was shot with my Hasselblad on Tri-X film.

At the time I was experimenting with a lab that offered to process the film for next to nothing. When I scanned the negative I thought it looked a bit grainy but put any doubts to the back of my mind. After I received the fax from the World Press Photo, (it was before the ubiquity of email) I instructed my printer to make a beautiful analogue bromide. A few days passed before I got a panicked call from the lab explaining the neg was impossible to work with. They actually said it looked like it had been developed in Urine. Photoshop and a digital output came to the rescue but I learned a valuable lesson; Never economise with your work.”

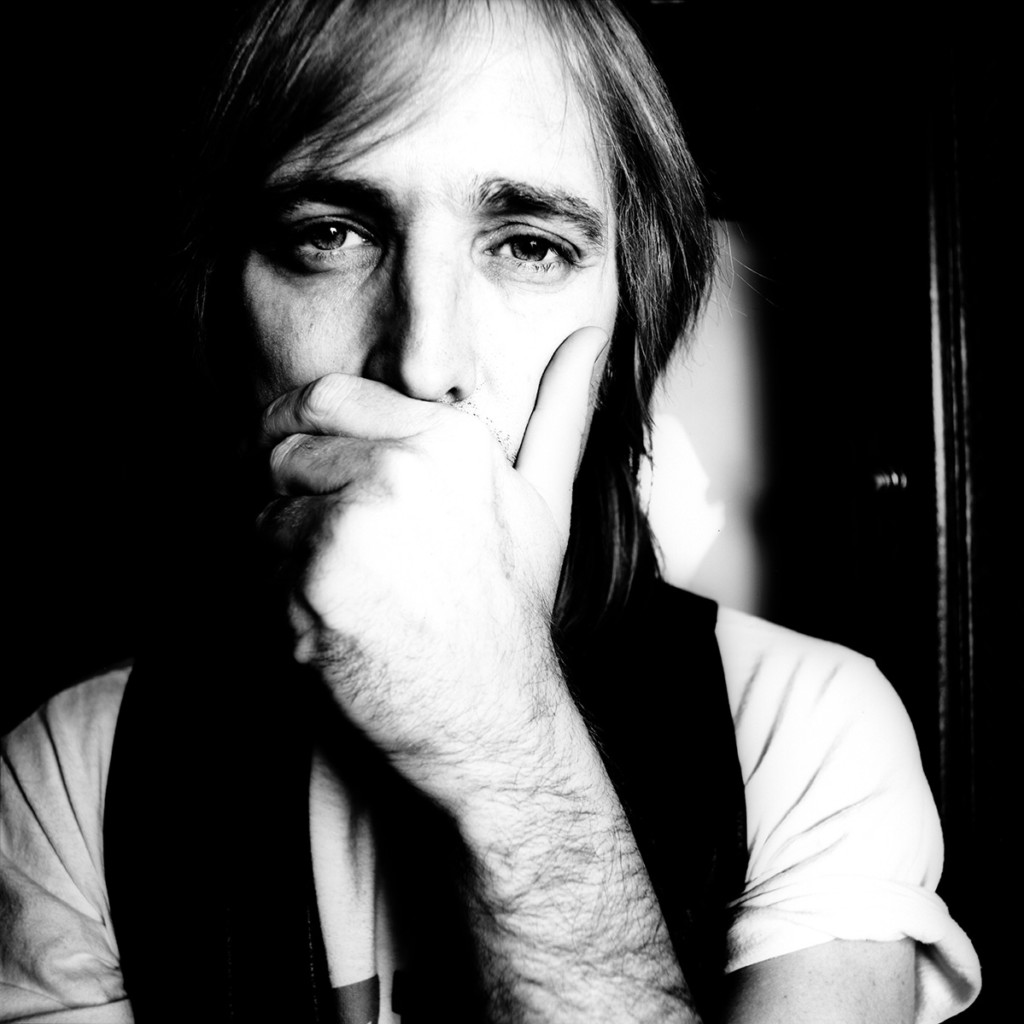

Tom Petty

New York, 1989

Tom Petty photographed in his NYC hotel room, 3 May 1989

Harry recalls the shoot: “This was my third commission from the NME. I remember the writer commenting that I was obviously making progress having been given my first transatlantic rock-star to photograph in New York. His label gave me a copy of his record Full Moon Fever and I played “Free Fallin'”constantly. Panicking in his cluttered hotel room, I ended up placing him in front of the giant television in a cabinet. I took a total of two rolls—24 pictures in total. This was shot on Kodac Technical Pan film developed in Agfa Rodinal with my beautiful Rolleiflex TLR 2.8 Planar.”

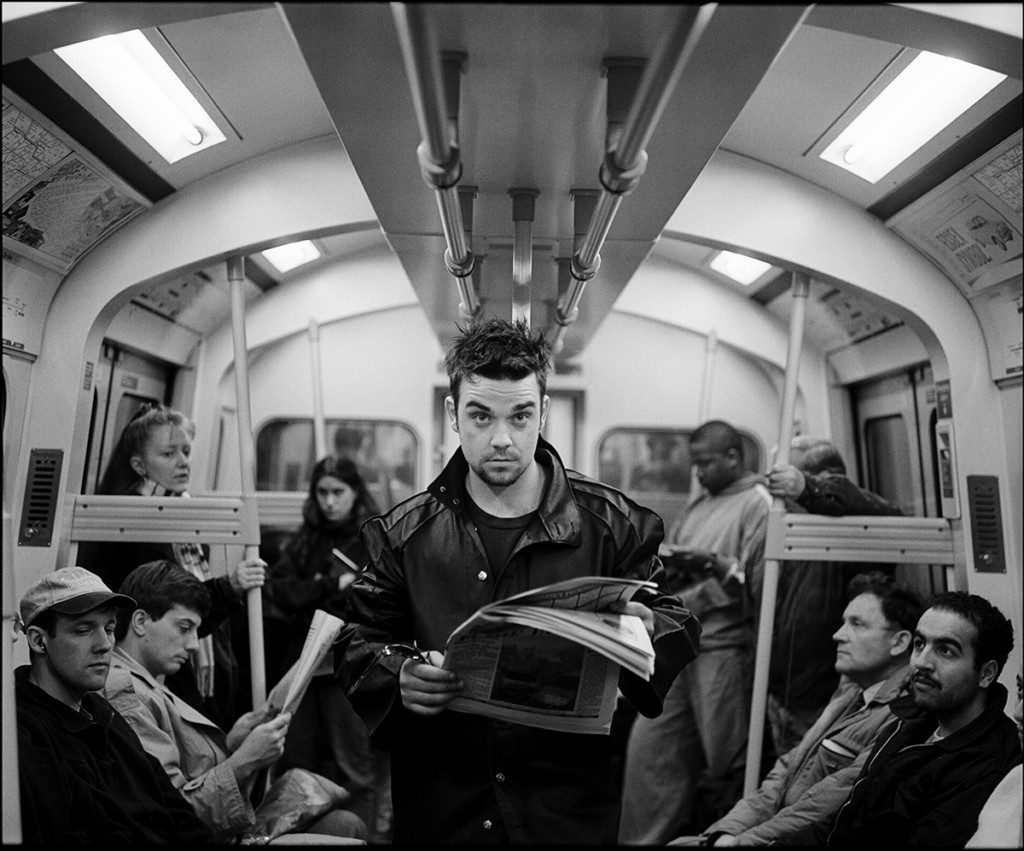

Robbie Williams

London, 1997 .

Robbie Williams, London, March 1997

Harry recalls the shoot: “In early 1997, Robbie Williams was at a difficult stage in his career, and it wasn’t easy to predict what would happen next. Aged 23, he had left Take That the previous year but had yet to release his first solo album. When I was commissioned by music magazine Select to photograph him in March 1997, he seemed a little lost.

The magazine had booked a studio in Clerkenwell, central London, and wanted me to shoot portraits to go with an interview by journalist Caitlin Moran. But Robbie wasn’t in the best frame of mind for the shoot. I remember clearly that I had little or no conversation with him. He wore an amazing striped suit, and I photographed him manically jumping around. It wasn’t an intimate type of shoot at all; it was just a bit crazy. His PR people were looking on and wringing their hands with anxiety. However, even in this unpredictable and dishevelled state, he was very charismatic and handsome. He had amazing eyes and was great to photograph.

Aside from the studio portraits, I had other plans for the shoot. I’m a big fan of Dennis Stock’s famous photographs of actor James Dean in Times Square, and I wanted to try something similar. I liked the idea of photographing someone charismatic in an anonymous setting, so I suggested that we go outside. The people from Robbie’s management company were very concerned about him being mobbed, but I tried to persuade them that it was a good idea. I said we would just walk through Clerkenwell to Farringdon tube station, where I’d get some shots of him on the concourse, perhaps reading a newspaper. They reluctantly agreed, though I didn’t tell them my real plan – to photograph him on a London Underground train. As Robbie and I walked through the station with an entourage behind us, I told him what I was planning to do, and he agreed. So when a train pulled into the platform, he and I jumped on just as the doors were about to close. Everyone else, including his PR people and my assistant, was left on the platform.

Robbie and I went one stop on the train to King’s Cross station. I had my Fujifilm GW670 (a 6×7 rangefinder camera with a 90mm lens), some Kodak Tri-X film and a tripod. I shot about 10 frames. Nobody on the train said anything to us or barely even looked up. We got out at King’s Cross and caught the train back to Farringdon. If I wanted to shoot something like that today, I’d probably have to get official permission or set it up with lots of extras. But we got away with it then because we did it so quickly. If you’re fleet-footed and completely brazen, quite often people don’t bat an eyelid. If you ask: ‘Is it okay to take the picture?’ you’re just giving people the opportunity to object. Here, we winged it and I think that energy and spontaneity is woven into the fabric of the picture. The best picture I’ve taken of him is the shot on the tube. It was selected for the 1997 John Kobal Photographic Portrait Award exhibition. It was exactly the picture I’d wanted. Even today, I can look at it and feel pleased that I managed to pull off my idea.”

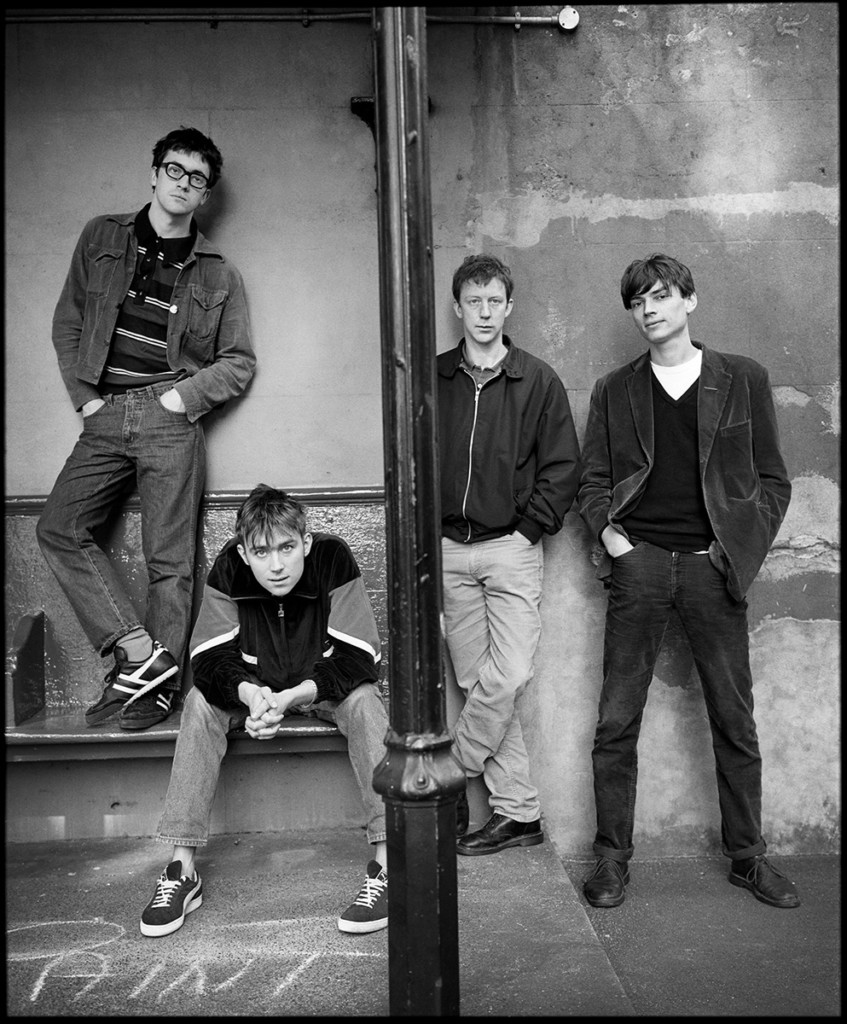

Blur

London, 1994

Blur photographed on Beaufort Street, Chelsea on 10 March 1994

Harry recalls the shoot: “This was a shoot for Select, the colourful Britpop magazine of the 90s.

First I took individual portraits in a studio behind the Bluebird restaurant on the Kings Road in Chelsea. It’s hard to believe now but the plan was to take these individual portraits and in post-production, colour each band member as a different race. I guess they wanted to illustrate the post-modern, multiracial Britain that the band celebrated. Thankfully the ‘black-face’ idea didn’t happen and they used this picture.

After the studio session, I took them for a walk down Beaufort Street towards the river. We strolled into a Victorian tenement block and I found this strange lean-to. ‘Wet paint’ was written in chalk on the floor and there was an inconvenient streetlamp obscuring my view but I think it worked as a location. I used the post to make two photographs in one, dividing the group into its constituent parts. I often don’t know what I’m looking for but intuitively know when I’ve found it.

When we got back to the studio, the mood was celebratory as we were shown the artwork for Parklife, their third studio album with the snarling greyhounds. The headline in the magazine declared them the best British band since the Smiths and 25 years on, maybe that doesn’t seem too hyperbolic.”

Seal

London, 1991.

Seal photographed on 23 April 1991 at his record label offices in London.

Harry recalls the shoot: “I took this photograph for the NME at his record label offices in Kensington Church Street. Such was my naivety at the time, when Warner Bros got in touch to ask about using a picture for press and publicity, I was flattered and agreed to a fee of £75. He went on to sell more than 20 million albums worldwide. I shot this on Agfa APX 100 with my Hasselblad.”

Susanna Hoffs

London, 1991.

Susanna Hoffs photographed on 25 February 1991 at the Meridien Hotel on London’s Piccadilly.

Harry Borden photographed Susanna Hoffs at the Meridien Hotel, Piccadilly for NME. The photograph shown above was used as the lead image for the article, an interview by David Quantick to promote her debut solo album, When You’re a Boy.

There’s a great quote in the interview with David Quantick, where he explains: “…Susanna wants to talk about her NME photo session. “I enjoyed it!” she beams. “It was fun! We just got creative with it. In The Bangles’ day, it was like – another photo session, four girls against the wall, let’s get it over with, kind of thing.” She frowns and then beams again. “But this one we had fun. It’s gonna look like Helmut Newton!”

Harry recalls: “Although her fame and beauty were intimidating, she was sweet and took my suggestion that she wear the hotel dressing gown we found in the wardrobe with good humour. I shot this with a Hasselblad on Agfapan 100 and Kodak Technical Pan, lit with a studio flash & brolley.”

P J Harvey

London, 1996.

PJ Harvey photographed in Harry Borden’s Bethnall Green flat, London 1996

Harry recalls the shoot: “Polly Jean Harvey is an alternative rock icon. She has won the Mercury Prize twice, had eight nominations for the Brit Awards, six nominations for the Grammy Awards and was awarded an MBE in 2013 for services to music.

I was commissioned to do a portrait shoot in 1996 with Polly by Option, an alternative music magazine of the time. I was a fan of her work, so it was an exciting opportunity. At the time she was popular in trendy circles, but wasn’t widely known yet. She was about as cool as you could imagine and I don’t think she’s ever lost that quality. Back then, I had a flat in London’s Bethnal Green and suggested we use it for the shoot. She turned up dressed completely in black, with green eyeshadow and red lipstick that accentuated her features.

We spent a few hours taking the pictures. I chose the green background to match her eyeshadow and complement her lipstick, and set up the backdrop in the hallway. I used natural light from a window, and set it up so that most of the light fell on her face while illuminating only a small part of the backdrop.

I shot this image on my Hasselblad CM with an 80mm lens. At that time, I liked a cross-processed look and this one was taken on Kodak Ektachrome Professional ISO 100 transparency film, and processed in C-41 (print film) chemicals. This produced a more contrasty image with little or no shadow detail. It was one of those occasions when cross-processing augmented the subject without being obvious.

Afterwards, when a limo came to collect Polly and take her back to where she was staying in Baker Street, I asked if I could go with her. There, we found a little supermarket and I took some pictures of her as an anonymous customer. The whole shoot was great because of the combination of an incredibly photogenic subject with amazing clothes and make-up. It was one of those portrait sessions which, when you get the film back from the processing lab, you’re really delighted with.

On a personal note, at the time of the shoot my wife and I were deciding on a name for our unborn child. I put the name Polly into the hat and my daughter was named after her.”

Richey Edwards and Nicky Wire

London, 1993.

Richey Edwards and Nicky Wire of the Manic Street Preachers photographed at Brompton Cemetery, London on 30 April 1993

Harry recalls the shoot: “My day with the Manic Street Preachers started with reportage black and white pictures of singer James Dean Bradfield with his cousin Sean Moore (drums) playing in a rehearsal room. The no-nonsense, engine of the band. Then later I went to Brompton Cemetery to photograph Richey and Nicky. Appearing louche, debauched and nihilistically glamorous, their contribution was a visual style that embodied the emotional alienation of the music.

I arrived at the location early and explored the temples looking for good spots. Entering one of the substantial mausolea, I sensed I was not alone. There were men standing in the shadows. My heart beating, I held my heavy camera bag to my chest and walked quietly out and was relieved to see the boys waiting for me at the Fulham Road entrance. It was early evening and the unsettling encounter was forgotten, as I began to take their picture in the smoggy London light. I gave them no direction, they just sat among the gravestones. I remember thinking how easy it was to photograph Richey. He was so handsome. Less than two years later he was to disappear at the age of just twenty-seven. On the eve of a promotional trip to America, he vanished from his London hotel room, his car discovered near the Severn Bridge. Sometimes images are rendered poignant as time passes.

Later I learnt the cemetery had a reputation for being a popular cruising ground for gay men so I needn’t have worried about being mugged for my cameras.

Shot for Select Magazine with my Hasselblad on Kodak Vericolor colour negative film developed in E6 to produce a transparency.”

Run DMC

London, 1998

Run DMC photographed near their Edgware Road hotel, London on 18 May 1998

Harry recalls the shoot: “ Often I find an environment I’d like to photograph anyway—like this wall by their Edgware Road hotel. I loved the flame-like markings. After placing my subject in the location, I see what happens. This was photographed on my Hasselblad with Kodak Tri-X. Sadly, Jam Master Jay (on the right) was shot and killed in 2002.”

Mark E Smith

London, 1993

Mark E Smith photographed in his room at the Pembridge Court Hotel, Notting Hill, London on 8 March 1993

Harry recalls the shoot: “Confrontational and curmudgeonly, Mark E Smith could be intimidating presence. It was a skill to get him to put down his cigarette and pint of lager and look at the camera. He was staying at the Pembridge Court Hotel in Notting Hill and I set up a little studio in his room.I did three shoots with him over the years and always enjoyed is abrasive mischievous humour.”

Dermot Morgan

London, 1998

Dermot Morgan photographed in Soho, London in February 1998

Harry recalls the shoot: “In February 1998, I was commissioned to photograph Dermot Morgan by The Sunday Times magazine. During the previous three years, the actor’s brilliant comic performances as the star of TV comedy series Father Ted had made him a household name. I was a big fan of the series and was looking forward to the shoot, but despite my determination to come away with strong pictures and my enthusiasm for the subject, this shoot didn’t quite go to plan.

I was usually allowed to decide on how I was going to photograph my subjects, but The Sunday Times had a specific idea for this shoot. They wanted colour shots of Dermot outside some sleazy establishments in London’s Soho. He was meant to strike some comic poses looking as if he had been caught out visiting the area’s strip joints and massage parlours, adopting a persona somewhere between his own and Father Ted Crilly’s.

I realised from the outset that this idea could be problematic: the people who operate these businesses were not likely to appreciate me using them as a backdrop. I was wary of the situation and tried to prepare, but at the time my wife had recently given birth and I was caught up in the maelstrom of caring for a baby and sleepless nights. It wasn’t until I had driven from my home in Hackney to Soho that I realised I’d left all my camera gear in my hallway at home.I hired a portable flash unit that I was going to use for fill-in flash. I tried to hire a camera from the same company, but they didn’t have any at the Soho branch. Trying not to panic, I went straight to a local Jessops and bought a second-hand Fujifilm 6×9 rangefinder. However, when my assistant and I connected the camera to the flash set-up in a Soho car park, we heard a ‘pop’, the flash started smoking and an acrid burning smell floated across. After that, it wouldn’t work at all. By then, the cold, drizzly afternoon was beginning to get dark. We were also running late. So, on the spur of the moment, I decided to do the entire shoot in black & white.

We met Dermot at his management company office in Soho. I covered up my technical problems when I met him, but was inevitably feeling stressed. Dermot himself was a nice man, very kind and compliant, and willing to go along with the idea of doing the shoot around Soho. The shoot lasted a frantic 20 minutes. There’s only so much you can do when you’re being shooed away from one sleazy strip club or massage parlour after another. By the time I shook hands with Dermot and said goodbye, it was beginning to rain but I was hopeful I’d managed to dig out a result, largely due to Dermot’s expressive features.

Just 10 days afterwards, I heard the shocking news that Dermot had died from a heart attack, aged 45, a day after he finished filming on the third series of Father Ted. It was so sad. My shoot was the last he ever did. When the photos were published in The Sunday Times, instead of illustrating a light-hearted feature, they were part of Dermot’s eulogy. Shooting in black & white had been forced upon me by my circumstances, but it gave the images a poignancy and authenticity they wouldn’t have had in colour.”

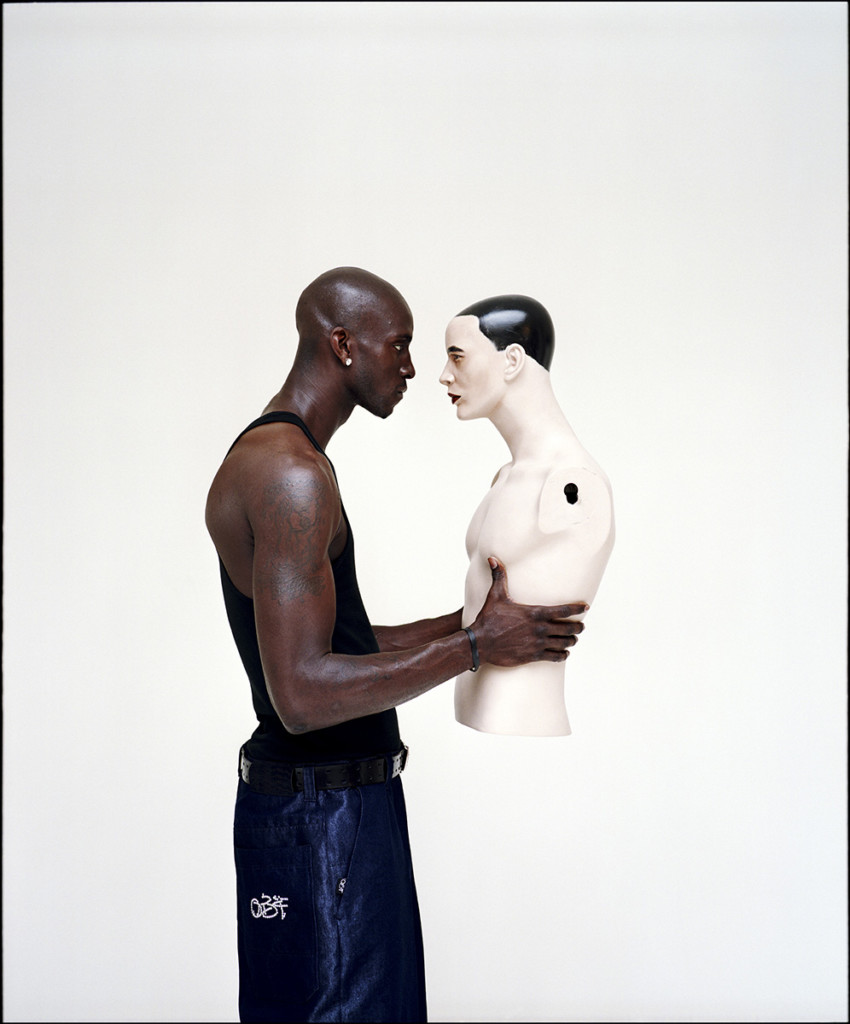

Kevin Garnett

London, 2001

Kevin Garnett photographed at Red Earth Studios, London, 2001

Harry recalls the shoot: “Shooting portraits of sports stars is often difficult. Unlike photographing members of a pop band, for instance, where they recognise a shoot is part of the publicity process, sports stars aren’t usually relying on photographers to promote them. For them, a shoot isn’t exciting or a novelty, it’s a pain in the neck. Therefore, in my experience, you’re often relying on their innate personality to get the pictures you want. Photographing basketball player Kevin Garnett, back in 2001, was a notable exception. That was partly because he’s a good-natured person, and partly because he was doing the shoot for an article linked to the launch of his own clothing brand. Kevin Garnett is a huge name in American sport. He played for NBA teams for 21 seasons, between 1995 and 2016, and is considered one of the sport’s true superstars.

I was commissioned to photograph him for American GQ magazine, so there was a good budget and I had the benefit of working with a stylist. I asked the stylist to provide some props that reflected the theme of making clothes, such as some tailor’s dummies and a pair of tailor’s scissors. The idea itself wasn’t particularly original, but it led to what I think is a very interesting portrait. The shoot took place in Red Earth Studios in London, which had a tall ceiling and a skylight which gave wonderful north light. I always got really nice results there, so I was pleased it was available when I got the commission. If you’ve got good available light and a subject like Kevin Garnett, you’re already halfway there.

Photographing Garnett was an extraordinary experience, partly because of his physical presence. He’s very much the alpha male, and at the time I photographed him he was just 25 and at his physical peak. He’s just under 7ft tall and very athletic, but perfectly proportioned – just much bigger than most people. His hands were huge and his arms were similar in girth to my thighs. I’m just under 6ft tall, but that extra foot makes a big difference and I remember having to stand on a chair to shoot at his eye level. However, he was very easy-going and playful, like a big puppy – at one point he got me in a headlock while fooling around – and was happy to do whatever shots I requested.

For me, the best shot came completely spontaneously, and mainly arose from Garnett’s playfulness. Most of the dummies we had were quite conventional, but one of them, which I think was possibly from the 1930s, had a weird look. At one point, Garnett picked that dummy up and turned it to face him. I took several shots, some with him looking towards the camera, others with his mouth open. But one shot, showing him staring intently at the dummy’s face, had something special about it.

My reading of that picture is that there’s an element of homoeroticism about it: one man is staring out another man in a very overt way. But it also has an interesting racial dynamic: the white dummy has an angry and hostile expression, yet it’s completely powerless. I wasn’t consciously aware of these elements when I took the shot and they’re the kinds of things you can only notice after taking a picture. This is the sort of moment that gets you really excited as a photographer. I really love that picture, it’s definitely in my top ten favourite images from my commissioned portraits. However, I’m pretty sure it wasn’t used in the American GQ article because it didn’t fit the idea of it being a fashion-led shoot. More contrived images can go down well with a magazine in the short term, but they don’t stand the test of time, because on some level they lack authenticity. Sometimes, a great picture just happens in front of you and you just have to be alive to it. “

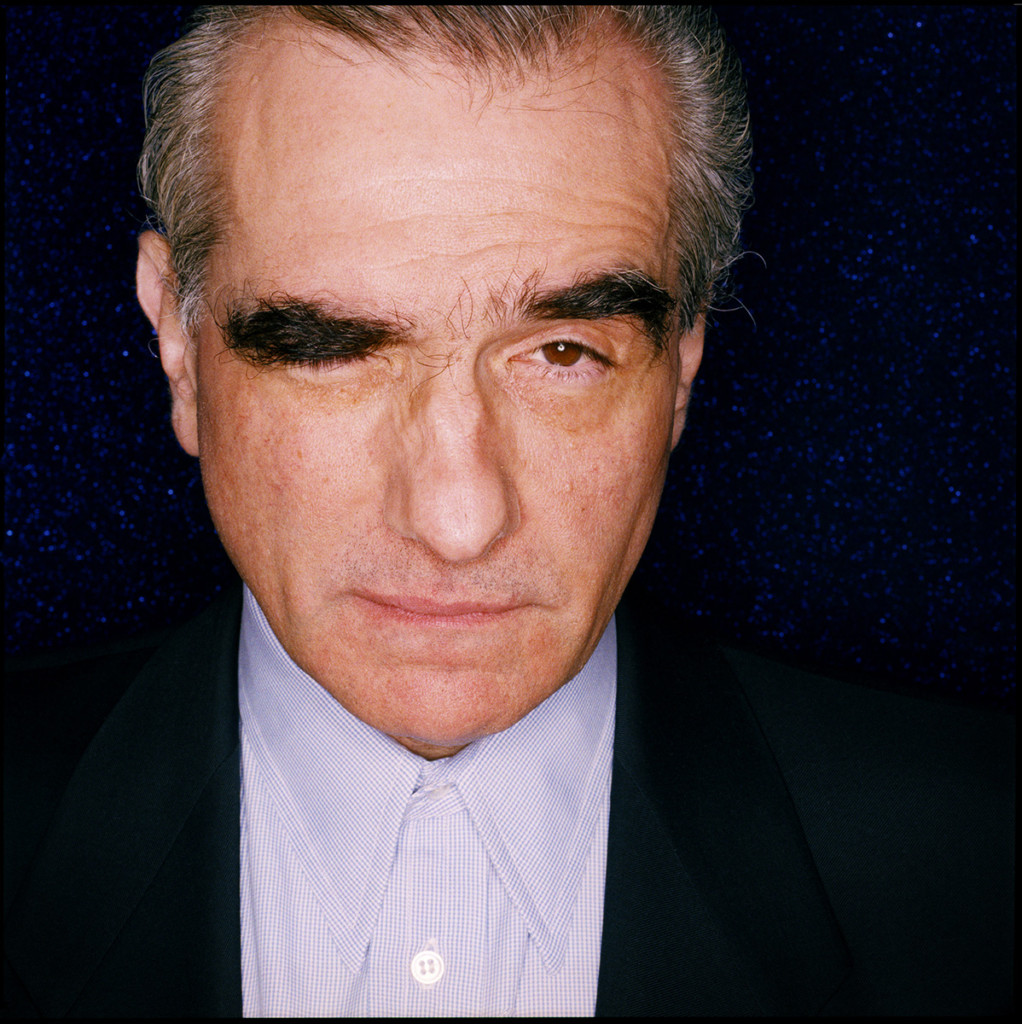

Martin Scorsese

London, 1998

Martin Scorsese photographed at The Dorchester Hotel, London,March 1998

Harry recalls the shoot: “In March 1998, Martin Scorsese was in London to appear at an event held by The Guardian. Scorsese was 55 at the time of the shoot and was firmly established as one of the major directors of his era for films such as Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, Casino and The King of Comedy. He’s a genius and undoubtedly one of my cinematic heroes.

The Guardian’s sister paper, The Observer, had a one-hour slot with him, during which he was to be interviewed by the journalist William Leith. Afterwards I would have about ten minutes to shoot a portrait. The shoot was going to take place in a suite at the Dorchester Hotel in London. Publicists repeatedly booked The Dorchester for interviews, so I could easily have ended up with lots of people against the same kind of background. Therefore I always took along either a roll of material or my black, white or grey backdrops. They provided a simple and plain alternative to a rather chintzy hotel environment.

Prior to this shoot, I went to Brick Lane in East London, where,at that time, there were a lot of fabric shops. I used to buy three metres of fabric and use it as a backdrop, which was much cheaper than buying a roll of Colorama paper. On this particular day, I found some sparkly blue material which had colours and textures that I thought might work well with a ringflash. While the interview was going on, I set up my equipment at the other end of the suite. I had loaded my Hasselblad CM (fitted with a 120mm lens) with a roll of Tri-X black & white film, and as Scorsese was saying goodbye to William Leith I took some informal shots of the director. I showed him a small portfolio of my work so he could see the kind of images I produced. He was quite macho; very smart, straight-talking and quick-witted; but friendly and jovial.

In that situation, it was an advantage that I had grown up with a Jewish-American father; he reminded me of my dad and so I didn’t feel intimidated. I just asked him what I wanted him to do. Scorsese was apologetic that we had so little time, and I think he would have given me a lot more time if he had been able to spare some. When he saw the roll of dark blue, sparkly material, he thought it was funny and knowingly said, ‘I see you’re going for the Vegas look.’ His movie Casino, released only a few years earlier, had been based in Vegas so it seemed appropriate. Sometimes, when I have very little time for a shoot I’m panicked into being more upfront about what I want from a sitter.

I was desperately trying to find an impactful picture, and I thought the most striking thing about his appearance was his amazing set of eyebrows. So, on the spur of the moment, I decided to ask him to wink as it made his eyebrows even more prominent. It’s not something I do often, but I have occasionally asked people to wink because it does make a good picture. I shot some with his left eye winking and some with his right, but the picture shown here worked best.

I only had time to shoot three rolls of film before Scorsese had to go: one roll of black & white at the end of the interview, then two rolls of colour; one of him at three-quarter length then a roll of head shots. The ‘wink’ picture has subsequently been syndicated all over the world, while the others were hardly published at all. It was recently used on a t-shirt for an event in Amsterdam. I think it’s one of the best ‘wink’ pictures out there, because he’s so cool.”

Gillian Anderson

London, 2012

Gillian Anderson photographed in the basement at 6 Fitzroy Square, London, 10 July 2012

Harry recalls the shoot: “One of my most enjoyable shoots in recent years took place when I photographed the movie, TV and stage actor Gillian Anderson. She is best known for being FBI agent Dana Scully in cult sci-fi series The X-Files. When I photographed her, in July 2012, I was aware of the series but had never watched it. This was a good thing, because it meant I wasn’t intimidated by her fame.

I was commissioned to shoot her portrait by The Sunday Times, which was running an interview with her to coincide with her role in the film Shadow Dancer. The newspaper had hired a location for the shoot: Six Fitzroy Square, an 18th century town house in London’s Fitzrovia. It had a lot of character and offered a range of interior backgrounds as well as an outside area.

Sometimes when I’m photographing actors I direct them as if they are on a film set. I ask them to imagine they are in particular situations and then photograph their expressions. With Gillian, for example, I did things like asking her to look startled, or to imagine she was seeing God in the sky. She was brilliant and really got into the idea. This was when I took my favourite picture of the day, in which Gillian has her mouth open as if she’s doing a silent scream. The image was shot against a white wall in the basement. I used two flash heads to light Gillian. One was a raw flash head, without any modifiers, which I used to backlight her. I put it in an adjacent room and used the door frame to flag it off slightly. I used the other head with a softbox, positioned to the right of my camera. I was shooting with my Canon EOS 5D Mark II and a 50mm lens.

The picture did well in various competitions and was shortlisted in the The Royal Photographic Society International Print Exhibition 2013. It also generated much discussion on Twitter, particularly among women. They were saying they liked the picture because it wasn’t retouched and showed her as a woman in her mid-40s, rather than trying to make her look younger. Looking at it now, the light is quite hard but it’s still flattering. I like the simplicity of the picture and its enigmatic quality. She appears vulnerable, as if momentarily surprised, and it seems like you’re witnessing a moment. In reality, of course, the moment was created, but its ambiguous nature means that everyone can bring their own interpretation to it.”

Bill Nighy

London, 2014

Bill Nighy photographed in the Sutherland Suite at the Connaught Hotel in Mayfair, London, February 2014

Harry recalls the shoot: “Bill Nighy’s roles in films including Love Actually have made him one of Britain’s best-known actors. His distinctive glasses are an integral part of his brand. In February 2014, he was about to appear on BBC TV in David Hare’s political thriller Turks & Caicos, the second part of the acclaimed Worricker Trilogy. As part of the publicity drive, he was being interviewed for Spectator Life magazine and I was commissioned to shoot the portraits. The venue was the Sutherland Suite at the luxury Connaught Hotel in Mayfair.

As always, I arrived at the location early and looked around the suite for good places to photograph him. I aimed to shoot with daylight most of the time, but also brought my lights and a tobacco-coloured backdrop. I’m always happy to do an environmental portrait and the hotel room suited that approach, but I had the backdrop just in case the hotel room was too cluttered. I also have black and white backdrops but felt they would be too sterile; the tobacco-coloured one was different and wouldn’t jar with what he was wearing.

Nighy arrived, looking magnificent in a classy suit. He was very charming and erudite, and was very clear about how he wanted to appear. As the shoot progressed, I remember learning a lot about tailoring from him because he was talking in detail about design features he did and didn’t like in suits. I wanted to take a classic portrait, something that would stand out. I put up the tobacco-coloured backdrop and did a few pictures. Then I looked more closely at his glasses—and noticed that by chance we were wearing exactly the same glasses. They were a vintage pair with black frames, made by Cutler and Gross, and I suddenly realised I was missing a potentially interesting opportunity to mess with his brand.

At that point I suggested he wear both my glasses and his at the same time. The idea was influenced by the photography of Asger Carlsen, who takes photographs that look like everyday pictures, but which are digitally altered to look strange or surreal. I was trying to do something similar but in-camera. I also decided to shoot him in profile, without showing his eyes. I was photographing him more as an object than a person – a familiar object, but one that has something unusual about it. I took the shot with my 50mm lens, with settings of 1/100sec at f/5, ISO 100. I lit him using a softbox.

I think the other people on the shoot thought I was going a bit off-piste when I took this picture. It was one of those occasions when I had got all I needed for the commission and I wanted something for myself. Realising we had the same glasses was a serendipitous moment – if I’d planned it beforehand and asked a stylist to find the same glasses, they would have found it impossible. I was really pleased with getting this completely unexpected picture. It wasn’t used by Spectator Life but was displayed in the 2014 Royal Photographic Society International Print Exhibition. This one has a twist and that’s why I have it in my portfolio.”

Baroness Thatcher

London, 2006

Baroness Thatcher photographed at The Lemonade Factory studios, Battersea, London, 9 October 2006

Harry recalls the shoot: “Like her or loathe her, Margaret Thatcher was a major figure in British life in the 1980s. She changed the country’s cultural and political landscape. My career as a photographer didn’t really take off until the early 1990s, by which time her political career was over. I never got the opportunity to photograph her in her pomp and glory, and thought I had missed my chance. Then in October 2006, I got a call from Time magazine. The editor was planning a special edition – 60 Years of Heroes – and my commission was to photograph Baroness Thatcher. Although by then I had photographed many famous people, getting this job was a brilliant moment in my career.

During our meeting she held my hand and asked me several times, “When are the other people arriving?” She clearly thought I was shooting all the ‘Heroes’ at the same time, as if Mikhail Gorbachev, Nelson Mandela and her would be rubbing shoulders in this shabby studio in Battersea (picked because of it’s proximity to her home). At the end she looked puzzled and said to me, “The others never came…” She was no longer ‘The Iron Lady’. Just a once-formidable person succumbing to human frailty as we all eventually do.

The ‘eyes-closed’ portrait was one of the last frames in the shoot and was taken using natural daylight. I hadn’t planned it. She just blinked and the idea for the picture came into my head. I asked her just to close her eyes. Even when I was taking the shot, I knew it was going to be an iconic picture. I used my Canon EOS-1Ds Mark II with a 50mm lens, with the camera on a tripod. The shoot lasted about 12 minutes.

What makes this portrait special? I think when you get someone to close their eyes, they’re in a position where you can observe them. They seem vulnerable. Margaret Thatcher had so much dynamism and power, so when you see a photo of her in old age, and with her eyes closed, there’s something absorbing about looking at her and reflecting on how she affected our lives.”

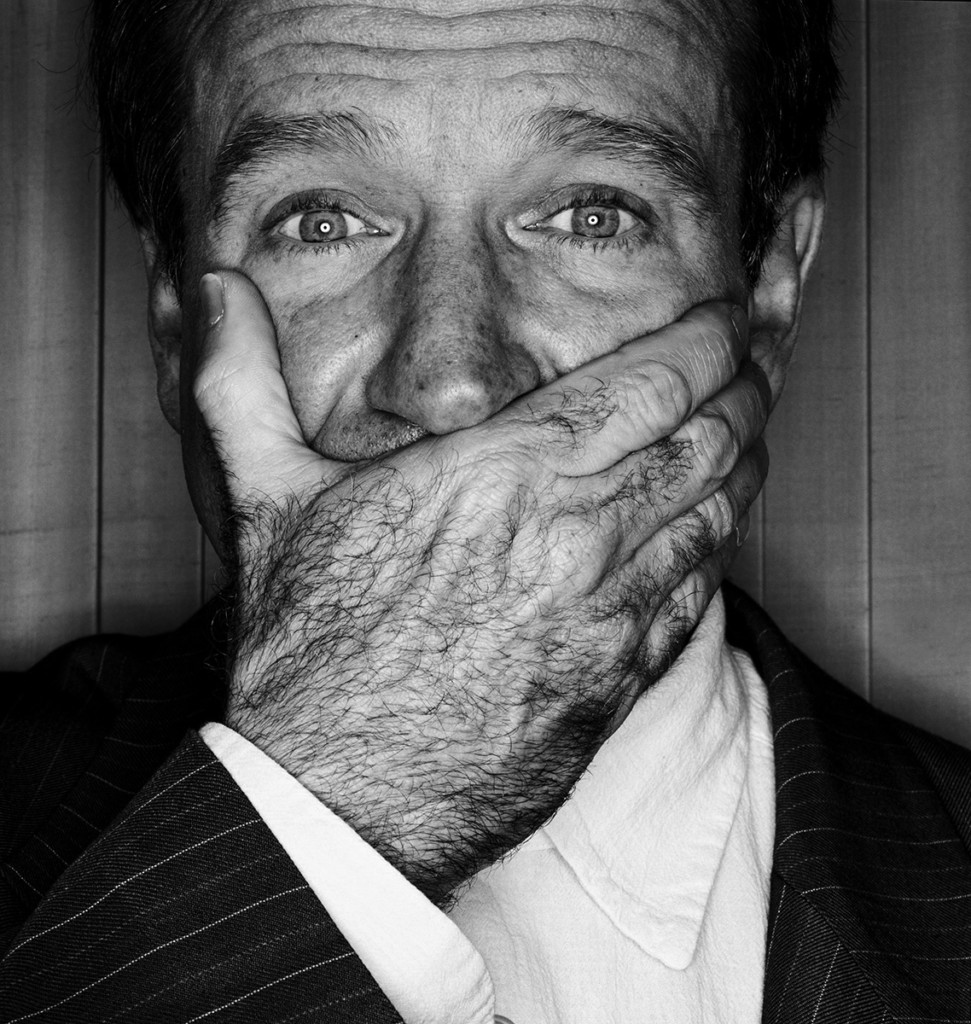

Robin Williams

London, 1999

Robin Williams photographed at The Dorchester Hotel, London, 1999

Harry recalls the shoot: “While I was on a trip to New York in 1999, showing my work to magazines there, I had a call from The Observer Magazine. I’d been shooting portraits for the magazine for a few years. This time I was offered the opportunity to photograph Robin Williams, who was promoting his latest film. The only catch was that I had to photograph him the next day at the Dorchester Hotel in London.

Following a string of roles in films such as Dead Poets Society, Good Will Hunting and Good Morning, Vietnam, Williams was a major star and this was an exciting offer. So I cut short my trip, booked the earliest available flight from the US and arrived in London the next morning. There, I met up with my colleague, journalist William Leith. The Observer told us we would have an hour for the interview and half an hour for pictures.

However, when we arrived at the Dorchester, Williams’ tough female publicist said, ‘You have half an hour for the interview and five minutes for pictures – if we have time.’ While taking in this news, we were led into Williams’ hotel room that was full of people. Williams had a big entourage, including a scary minder who was completely lacking in any warmth or sense of humour.

The entire atmosphere felt rather intimidating. After the interview, I started shooting portraits. I was using a Hasselblad CM, a medium-format film camera. The lighting in the room was poor so I used a big Bowens ring flash. Although time was really limited, as I was trying to shoot the portraits, Williams talked constantly. While I was being hurried along, he was doing his shtick and trying to entertain everyone in the room. I found it really irritating. He could have said, ‘Give this guy a break and let him do his job,’ but he just shrugged his shoulders as if it was nothing to do with him and let other people be nasty on his behalf. So I had to persevere.

As a passive-aggressive way of telling him to shut up, I asked him to put his hand over his mouth. It was also a way of getting his very hairy hands in the picture, which I’d first noticed years before when he acted in Mork & Mindy. I got one frame of him in that position, then he put his hand down. This was the most interesting image from the few rolls of film I managed to shoot. You can see the use of the ring flash by those distinctive ‘doughnut’ shapes reflected in his eyes.

In that kind of situation, where I have very little time, I usually keep taking pictures for as long as I can. However, in this case it was starting to annoy the people in the entourage and further sour the atmosphere. When I took out my Leica and took a couple of reportage-style shots, tempers started to fray. The minder threatened to throw me out of the window if I didn’t stop and the shoot came to an abrupt end. I had rapidly shot four 12-shot rolls – two black & white and two colour. Even though my portrait of him was taken in a brief, frenzied and ultimately unhappy shoot, it’s still one of my favourites.

Rosamund Pike

London, 2006

Rosamund Pike photographed at Jasmine Studios, London, September 2006

Harry recalls the shoot: “For me, improvisation is a vital part of the creative process. When I’m shooting a portrait, I enjoy looking for something that hasn’t been done before and ending up with images I hadn’t anticipated. I believe it’s better to react to what’s around you and riff off things, because then you get the unexpected. That’s what happened when I did a portrait shoot of the actress Rosamund Pike in September 2006. I had been commissioned to photograph her for the Sunday Telegraph magazine, to illustrate an interview. At the time, she was 27 and in the early stages of her successful screen career, following her debut in the Bond film Die Another Day four years earlier.

The shoot took place in Jasmine Studios, which was a studio complex in Shepherd’s Bush, West London. It was a great location which had really good daylight, which I generally prefer to use, and was equipped with lots of other light sources. I arrived at the studio at 9am with my assistant, and was met by a stylist and racks of clothes to use in the shoot. While I was waiting for Pike to arrive, and afterwards when she was in hair and make-up, I anxiously paced around the outer areas of the studio. Whenever I do a studio shoot, I always walk around the immediate area to see if there are interesting places I can use.

While I was wandering upstairs, I found I could get access to a mezzanine floor that looked directly down on the studio. I wondered if I could use that viewpoint in the shoot. As I had the whole morning to work with Pike, I did a variety of different shots, from tight close-ups of her face to wider shots where she was just one of many elements in the picture. I mainly used daylight, but in some I used a big Octa softbox for flattering light and a Quantum flash, which gives a much harder light.

Pike is genuinely beautiful, with almond-shaped eyes. I thought she looked like a kind of British, prim Brigitte Bardot. Her experience as an actor means she’s comfortable taking direction and adopting a range of personas, poses and facial expressions. She’s very intelligent, but at the same time there’s a kind of brittle coldness about her. As the shoot progressed, I was pleased with the pictures I’d got, but still wanted to try shooting from the mezzanine floor. I took some shots of her from that viewpoint, sitting in a chair surrounded by lights. Then I decided to try a simpler image with her lying on the floor with the tangled black cables of the studio lights at the top of the frame.

I would be embarrassed about asking somebody to lie on the floor unless I was sure it would make a really good picture. Making someone feel uncomfortable would be excruciating for me. It was just a question of having the strength of my convictions and asking her to do it. As it turned out, she happily agreed. She lay in different positions, but the one I liked most showed her looking to one side, with her arms above her head and both her hands and feet crossed. The pose in this picture is relaxed and psychologically submissive, but the fact that she’s crossed her hands and feet suggests she’s keeping something back.

Rosamund Pike is beautiful and famous, so any professional who photographs her really has to get something good. However, although there are lots of portraits of her around, this one is special to me. It was later included in the RPS International Print Exhibition for that year. Even if it had been a more lavish shoot, I don’t think I’d have got a better picture.”